7. Controlling selection structure and tables¶

In this part of the tutorial we’ll learn how to control the way a selection is structured and joined together and how to change which table the selection counts.

Joining more than two selections together¶

We can use the & | ~ operators we saw in the previous part

to build more complex selections made of multiple parts:

>>> low_price_deals_audience = eligible_for_discount & ~high_earners

We could have even written the eligible_for_discount variable directly

using its constituent parts:

>>> low_price_deals_audience = (student | under_21) & ~high_earners

Here we’ve had to use parentheses

so that the student | under_21 gets combined first,

before the selection resulting from that is combined with ~high_earners .

Without parentheses, Python’s operator precedence rules

mean this would be calculated as:

>>> not_what_we_meant = student | (under_21 & ~high_earners) # since & takes precedence over |

Even if operator precedence means that your selection would resolve as intended without parentheses, it’s probably sensible to include them to be explicit and improve readability:

>>> either_of_two_pairs = (student & smiths) | (high_earner & under_21)

The & operator ‘binds’ more tightly than the | operator,

so this selection would resolve in the same way even if the parentheses were omitted.

But including them makes the logic easier to read

and enables you to communicate your intent to anyone else reading your code.

Determining the resolve table¶

The resolve table simply refers to the FastStats system table that the selection is set to count records from. As mentioned in the previous part, this is determined automatically according to the following rules:

for a selection consisting of a single ‘clause’, it is the table that the variable in this clause belongs to

for a selection made from a combination of several ‘clauses’, it is the table of the first (i.e. left-most) clause

normal Python operator precendence applies, including expressions in parentheses being evaluated first

The following code demonstrates this:

>>> student = people["Occupation"] == "4"

>>> usa = bookings["Destination"] == "38"

>>> student.table_name

'People'

>>> usa.table_name

'Bookings'

>>> (student & usa).table_name

'People'

>>> (usa & student).table_name

'Bookings'

So if your selection uses elements from different tables, make sure you begin it with an element from the table you want to use for the overall count.

Changing the resolve table¶

We can also manually change the resolve table of a selection

using the multiplication operator * with the table:

>>> been_to_usa = people * usa

>>> been_to_usa.count()

273879

>>> been_to_usa.table_name

'People'

Note

The table that we ‘multiply by’ needs to be a Table object.

Using the string of the table name will not work.

Again, we can use parentheses to group different parts of the selection to control how it is structured:

>>> audience_1 = people * (usa & at_least_2k)

>>> audience_1.count()

12746

>>> audience_2 = (people * usa) & at_least_2k

>>> audience_2.count()

20098

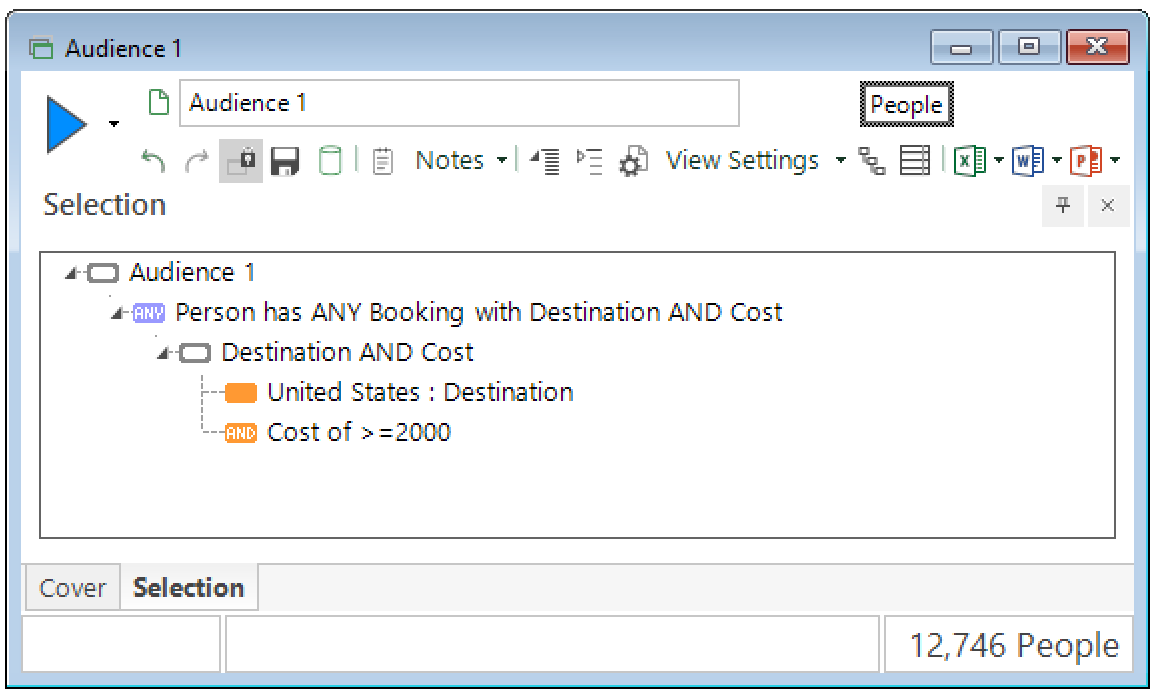

audience_1 selects people who have any Booking to the USA costing at least £2000

— the usa and at_least_2k clauses are grouped together with parentheses,

so a person must have a single Booking matching both criteria to be selected.

It is equivalent to this selection in FastStats:

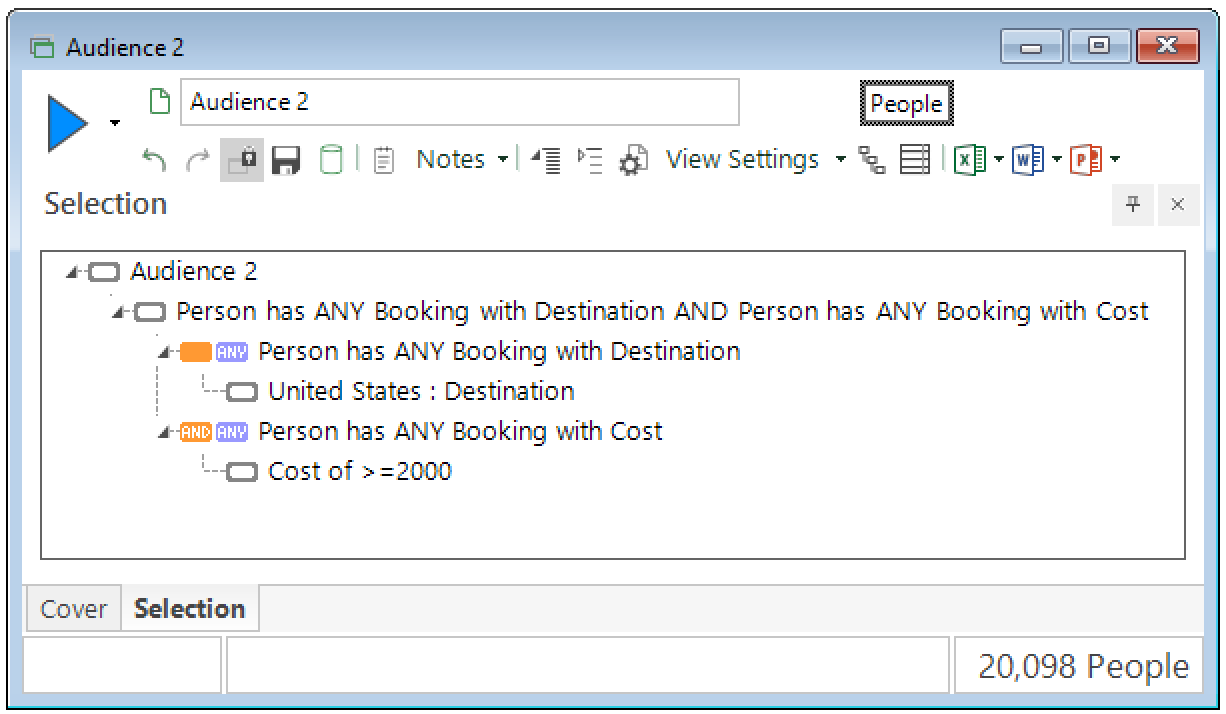

audience_2 selects people who have any Booking to the USA,

and have any Booking costing at least £2000.

The difference is that the conditions don’t have to apply to the same booking

— the person’s Booking to the USA could cost less than £2000,

as long as they have another Booking that does cost at least that much.

Here’s the equivalent selection in FastStats:

A worked example¶

Let’s just remind ourselves what audience_2 looked like

and work through step-by-step how it’s evaluated, according to the rules above.

>>> audience_2 = (people * usa) & at_least_2k

(people * usa) is evaluated first because it’s in parentheses.

usa is a condition on the Bookings table,

but using the * operator on it with the People table manually changes it

to resolve to the People table.

We could re-write this part as a new variable:

>>> audience_2 = people_to_usa & at_least_2k

Working left-to-right, people_to_usa is clearly a selection on the People table

so at_least_2k is automatically adjusted to resolve to the People table to match.

We could re-write this behaviour explicitly as:

>>> audience_2 = people_to_usa & (people * at_least_2k)

If we ‘unzip’ people_to_usa to its original form, we get:

>>> audience_2 = (people * usa) & (people * at_least_2k)

which mirrors the structure of the equivalent selection in FastStats shown above.

So far we’ve only interacted with our data by counting selections, but in the next part we’ll learn how we can use data grids to create an export of our data, which we can analyse further.